After my recent visit to Japan, I decided to reread One Straw Revolution as well as his other book The Natural Way of Farming1. Without a doubt Masanobu Fukuoka’s true masterpiece on the philosophy of Natural Farming was One Straw Revolution. Although the book is now 50 years since its first publication, much of what he wrote about in regards to modern, scientific farming then is still true today - in fact, in many respects, the situation2 has become much worse. There is always hope, and the positiveness that comes with a new generation of farmers and foodies, a path of resilience, is one where nature still provides farmers with a light at the end of the tunnel. But, as he wrote in Natural Farming, we need to transcend the here and now and begin to see the world from the broader, cosmic perspective.

Although 50 years has passed since One Straw Revolution was published3, we’re still having many of the same discussions, facing the same problems, and proposing many of the same solutions. Yet, the problems aren’t the same, therefore nor are the solutions. The Earth’s population has increased by 120% since 1970. Climate change and global warming is no longer a theory. Soil loss, biodiversity loss, and the despoliation of the planet is accelerating despite all of the advances and knowledge-gain we’ve made. And now we have to contend more deeply with the politics of global despoliation - the destruction of Nature. Perhaps we’re tilting at windmills, but we have to work towards nature and not away from it if there is to be a sustainable future.

Masanobu Fukuoka practiced his style of “do nothing“ agriculture/farming for almost his entire life. Much of what he did, wrote about, and taught others has been practiced, translated, and re-translated into many times over. Even the approaches and philosophies of today’s regenerative agricultural movement cohere to what he preached and how he farmed. There is nothing really new about this approach.

Fukuoka’s style of farming was not something he dreamt up one day. It was based on how he saw and experienced the world around him. He was witnessing, as many others were at that time, the despoliation of Nature in favor of destructive practices foisted upon farmers through the false pretenses of chemicals, machinery, technology, fossil fuels, and false promises.

His ‘do nothing’ philosophy countered this unwinding of Nature and was built on a foundation of farming a particular way in Japan and Asia for thousands of years. ‘Do Nothing’ farming is based on four principles: i) no tillage, ii) no weeding, iii) no pesticides, and iv) no fertilizers4. But it took Fukuoka years to get to a point where he could call his style of farming “Natural.” He failed many times. To be sure, there are no overnight sensations in farming. We all fail, its the getting up part that’s important.

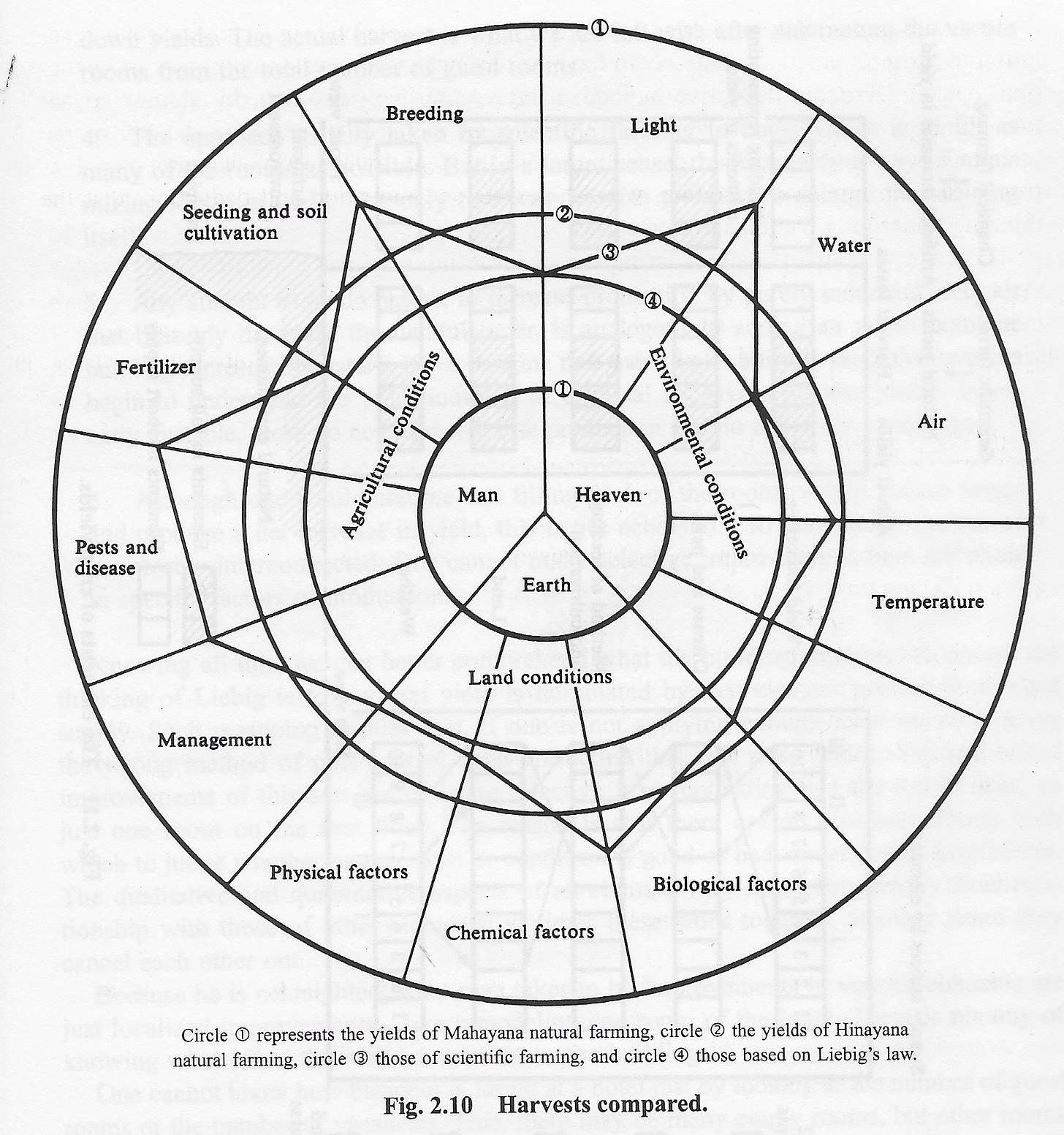

Scientific farming, a term he used and what we call industrial farming today, and is an approach where the farmer is totally disconnected from nature. He also referred to this a discriminatory farming. Mahayana farming - an advanced Buddhist approach - was the highest level of natural farming one could achieve, one where the farmer was totally connected to the world or Nature around them. He also referred to this as non-discriminatory farming. Hinayana farming was a middle road approach. Where one sought out and practiced a nature-based farming approach but still utilized some discriminatory thinking and practices. I suggest that most holistic growers I know are on the middle path - more Bodhisattvas5 than Buddhas.6 The diagram below gives an idea of how Fukuoka viewed the four methods7 in terms of yield.

from The Natural Way of Farming: The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy. Masanobu Fukuoka. Published 1985, Bookventure, India

I can’t tell you that there’s one discrete thing from One Straw Revolution or any of his other works that applies better today than any other. It’s the unfortunate truths that are still true and his philosophical approaches interwoven with practical ideas that need to be picked up by farmers everywhere. But that doesn’t mean trying to apply a philosophy for farming rice on a quarter acre of land in Japan to farming 10,000 acres of wheat in North Dakota will work. No, in fact he based much of his work on the production of rice, a staple crop in Japan, as well as citrus. The thrust of his work was to catalyze a mindset shift and encourage the right-sizing of agriculture so that more people are farming with Nature on smaller pieces of land once again. And though I’d like to think that we are starting to see a shift here in the US, on the whole we’re still too attached to the financial-economy part of agriculture, and not focusing on the nature economy. In following a “do nothing“ path of agriculture, progress can be made in a way that benefits all of humanity.

What Does This Have to Do with Radical Pomology?

For everything that’s still true from One Straw Revolution, there’s is also plenty that’s not. Times have changed. People have changed. The tools have changed. Our ability to understand the world around has increased several magnitudes from Fukuoka’s time. But what hasn’t changed, and what he essentially was warding us away from was our love affair with secular or scientific farming and our disconnection with Nature.

Fukuoka was not wrong, though he was at times seemingly contradictory in his writings. Pruning, for example, is one area where he describes the practice as resulting in a confused tree. And in another area he wrote that pruning was a necessity to avoid a confused tree. What he was really saying is that if you start out early in a tree’s life by pruning it, you’ll be pruning it its entire life. Allowing a tree to come into its natural form naturally and observing his growth habits, you’'ll understand its true form and therefore “know” better how to prune the tree more naturally for health, productivity, and longevity. He put pruning, as he did many other orchard practices, within the context of being conscious of the tree’s natural form and habits, thereby knowing whether it’s growing true, and how best to prune it. But by leaping in before knowing anything, or simply by using bad technique, you cause problems that will be with the tree for years.

The bottom line is that despite his seeming contradictions there is basically nothing in his writings that I can find, even if interpreted under current times and conditions, is blatantly wrong. When it came to pruning and other things with natural farming he not just encouraged, but required us to be observant and to be conscious in a way that transcends time and space in order to see the true nature of the whole and the beauty of the universe8. In this way, we can come back to the physical manifestation of that cosmic oneness in becoming better farmers. Not by “doing nothing,” but by applying our connections with the natural world in the “right” way to the benefit of the tree, the orchard, the entire farmscape ecosystem. Right mind, right pruning. Fukuoka may have said ‘do nothing’, but he really meant to do as little as possible - Nature will take care of the rest.

The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy

Loss of soils, biodiversity; the effects of climate change; technology creep; loss of farmer autonomy; etc. has all become more dire.

And to be sure, it was based on his experiences and observations 60, 70, and 80 years ago,

and for fruit trees: “no pruning.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bodhisattva

The fourth method he described was Liebig’s Law of Minimum.

The Tao of Tree?

Dear Mike,

Thank you for these thoughts! Reading Masanobu Fukuoka's books in the late 70s was a revelation for me as well. I would like to share my thoughts from being an herbalist for 40 years and living, working and learning from the Green Kingdom. It is clear you already share the concept that Nature is alive, not just in the sense of carrying on respiration and photosynthesis and other biological functions, but ALIVE. Thinking, feeling, aware and able to communicate....

IF we can become quiet enough and humble enough to listen. In my interactions with any plant, (herbs, vegetables, fruit trees) I always stop first and acknowledge them, thank them, and ask their permission WHATEVER it is I want to do. Then I listen- and FEEL what the plant has to tell me. Maybe it sounds a bit flaky (or maybe I ate too many mushrooms back in the day) but the plants always respond....sometimes we are just in too much of a hurry or too hell bent to pay attention.

I've always been a "middle road" gardener....weeding out only that which might interfere with the growth of the plant I am trying to grow and leaving all the rest. (if only people could exist in harmony like the "weeds" do) It leaves a beautiful symmetry of weeds, flowers and vegetables that all exist in perfect harmony with each other. Again...I always talk to the "weeds" asking permission, explaining what I am doing and WHY and most of the time use those "weeds" as medicine. Usually, it's all good - but once in a while, I will get a "NO that's not ok" and I leave the plant there. Sometimes later on I understand why-sometimes not but it doesn't really matter.

The wild apple trees here on the property have taught me a lot. First of all, that they don't really need me at all, ( ha ha) but I have found that they really DO like being acknowledged and thanked and they seem to have responded positively to the wee bit of gentle pruning I have done. ( not what most orchardist consider pruning). I am sure no scientist would say an apple tree can feel grateful, but I beg to differ! And maybe it's not even the act of pruning, maybe it's the love and affection and gratitude I pour out to them when I am working WITH them...not trying to be in control of them. Masanobu pointed out that a fruit tree will basically grow in perfect symmetry without any help. But MAYBE cutting out the dead or diseased branches helps them in a way they can't do themselves. Can a tree feel appreciation? I say yes. Maybe cutting the branches that rub on each other or thinning out ones that are all in a tangled mess helps them too. But who stops to ask the tree?? Not trying to promote this idea as right or wrong, I just FEEL that the trees I have done this with seem to be genuinely radiant with appreciation.

Last winter, a "Master Orchardist" came to my neighbors property and "pruned" the trees.

I was aghast and horrified at how he mangled them. I will send pictures at some point. The trees CLEARLY did not like what he did and yet there was nothing they could do to stop him. And he never even noticed how radically he ruined their perfect balance and symmetry and harmony.. (Thankfully, I had asked my neighbor to please leave the Michael Phillips tree alone and let me prune it so it did not suffer the same fate.) ANYHOW, all this ramble just to offer another way of looking at this subject. Maybe not one extreme or the other, and maybe acknowledging what the trees have to say about it all!

All the Best to you!

Namaste

Holly